Sequential Circuits

All of the circuits we have considered so far have been acyclic; this was an essential part of the definition of a combinational circuit. In general, if a circuit has a cycle, its output behavior might not be well-behaved—consider the simple example of a NOT gate whose output feeds back to its input, so that if the output went high, it would be forced low after one gate delay, then back high after another delay, etc.1

In this section, we will explore two ways of adding cycles to circuits in a controlled fashion. The first, operating on the level of just a few gates, will give us circuit components with memory. The second, using larger-scale feedback on circuits that include both combinational and memory components, will give us a means of implementing state machines and, ultimately, general-purpose processors. On the larger scale, the circuits will be what are known as synchronous—that is, a clock signal is used to synchronize the times at which feedback is applied. At the small scale, we will start with asynchronous circuits, where feedback may arrive as soon as the gate delays permit. While it is possible to design large-scale asynchronous circuits, we will not be considering that here.

Circuits with cycles are known as sequential logic circuits, because the output depends on the particular sequence of inputs the device has received in the past; unlike combinational circuits, the output is not solely determined by the current combination of input values but potentially by the entire history of inputs (in other words, it is not purely functional—its behavior depends on side-effects). As a result, they can be considerably harder to reason about, and we will need good abstract models, such as state machines.

Memory Devices

Although the circuit with one NOT gate feeding back on itself is unstable, a cycle of two NOT gates would be fine:

Whatever the output is at , the output at will be the opposite. Each one feeds back and reinforces the other, and the circuit is stable. Unfortunately, it is not very useful—there is no way to provide input to change the value .

By replacing the NOT gates with either NAND or NOR gates, we get a circuit known as a latch. Here is the diagram for a so-called latch:

When the inputs (set) and (reset) are both 1, the latch behaves just like the circuit with two NOT gates (because ): whatever the output is at , the opposite value will be at (hence its customary label—it is the negation of ).

When the input is 0, the output is forced to 1—the latch is set (the label suggests that it is "active-low": the latch will be set when the input is false). Again, because of the feedback, when is 1, will be 0. Returning to 1 will then leave the latch in the set state. This is where the sequential nature of the latch shows: its state depends on its past history (in this case, the fact that the set line was most recently active).

When the input is 0, the output is forced to 1 and correspondingly will become 0—the latch has been reset. Again, returning to 1 will leave it in the reset state, until the set line is next activated.

If both the set and reset lines are active (0), then both output lines will be forced to 1. This presents two problems: it violates the property that and are complementary, and it sets up a potential race condition if both lines are restored to 1 at the same time. When the inputs become 1, exactly one of the outputs can be high; however, which one "wins" the race will depend on the precise timing of the transitions from 0 to 1, and potentially also on slight imperfections in the gates (if one of the NAND gates responds slightly faster than the other, for example). So, don't do that.

The latch is what is known as a transparent latch: the output responds as soon as the input is changed. To make sequential design easier, we frequently want memory devices that will only respond at certain times. By adding an extra layer of gates to the input, we can make what is known as a gated D latch. The inputs are (data) and (enable):

As long as is 0 (note that this is now an active-high device), the and inputs to the latch will always be 1, regardless of the input. The gated D latch is only enabled when the input is 1. When enabled, the latch becomes transparent: if is 1, then will be 0, and the output will be set to 1; if goes to 0, then will be 0 and the latch will be reset. There is no combination of inputs for and which can make both the set and reset lines active at the same time, so we don't have to worry about that case.

When the enable line returns to 0, the gated D latch will remain in whatever state it last entered. Here is a truth table for the latch, together with its common symbol when used in a circuit:

| 0 | X | hold | hold |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

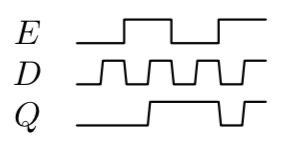

When dealing with a sequential circuit, it is often helpful to look at a timing diagram, which shows the levels at various points of the circuit over time (increasing from left to right). Here is a timing diagram for the gated D latch, which shows that the output is transparent to the input only when is high:

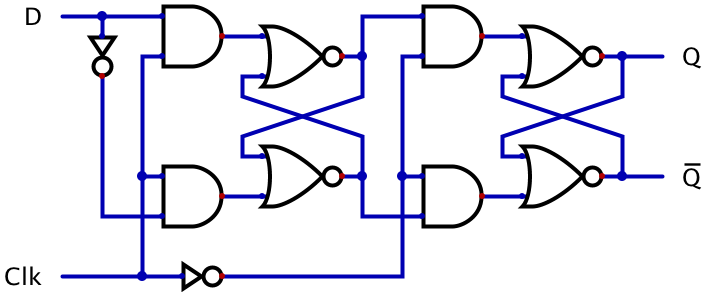

Instead of a latch, it is more common to use a device known as a flip-flop. The distinction from a latch is that a flip-flop will only respond to input for a very brief time; it is what is known as a clocked device, since it will only change its state when a clock pulse is received (typically, just as the clock pulse is rising from 0 to 1). In synchronous logic design, the entire circuit will use a single clock signal, so that each clock pulse advances the state by one step (and the state has time to propagate through all the gate delays before the next pulse). Here is one design for an edge-triggered D flip-flop:

Just as the gated D latch modified an latch by adding a layer of two NAND gates, this flip-flop modifies an latch by adding a layer of two input latches. In each case, the input layer protects the output latch from entering the illegal state (when both and are low).

The idea is that, as long as the clock (Clk) is 0, the set () and reset () lines of the output latch will stay high (inactive). The line marked will be whatever is, and the line marked will be the opposite, . Although one of the input latches will be in an "illegal" state, the output latch will not be affected.

When the clock goes to 1, the input latches will resolve to consistent states: will be , and will be . That is, if was 0, then the output latch will be reset, while if was 1 it will be set. However, once the clock reaches 1, further changes to will be ignored: if the lower input latch is reset ( is 0, meaning was 0 at the rising edge), then changing will leave it in the reset state; if instead the lower input latch is set ( is 1, meaning was 1 at the rising edge), then changing will switch it between the set and illegal states (where is still 1), and the upper input latch will stay in the set state.

When the clock goes back to 0, the output latch will continue to hold whatever state it had (because both of its inputs will be 1 again), until the next time the clock rises.

The only danger with this design is if is changed at exactly the same time as the rising of the clock signal, because then if one of the input latches was in an illegal state it is possible to have a race condition. Designers avoid this by arranging for the input to be stable for at least a brief "setup and hold" time around clock pulses.

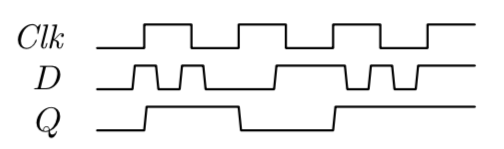

Here is a timing diagram for the D flip-flop, and its common circuit signal (the input marked with a triangle indicates that it is a rising-edge-triggered clock):

Rather than a truth table, it is useful to give what are known as a characteristic table or an excitation table for a flip-flop. The characteristic table shows how the input () and current state () lead to the next state () after the clock pulse:

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

The excitation table presents the same information, but from the viewpoint of "given a current state and desired next state , what does the input need to be?"

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

Here is another implementation of the D flip-flop with a somewhat easier-to-understand circuit (although it uses more gates):

This is known as a main-secondary design, because it consists of two latches (in this case, they are latches, made with NOR gates, so the set/reset actions occur when their inputs are high2), each of which is enabled for half of the clock cycle. When the clock is high, the first ("main") latch stores the incoming data signal. It is transparent during this time, so if the data is changing then so will its state. When the clock goes low (so this is a trailing-edge triggered flip-flop), the secondary latch is enabled and it copies whatever was stored in the main latch at that instant. Although the secondary is transparent during its half of the clock cycle, its input will not be changing because the main cannot change while it is disabled. Therefore, the flip-flop only changes its state at the instant the clock goes from high to low. There is still a race condition possible (it can be shown that there is no flip-flop design without a race condition), if the input changes just as the clock goes low.

The first electronic latch was the Eccles-Jordan trigger circuit. Patented in 1918, it was built out of two vacuum tubes connected in a feedback loop. In the early 1940's, Thomas Flowers (1905–1998) used his experience with telephone switching circuits to build Colossus, one of the code-breaking machines at Bletchley Park. The Colossus design used the Eccles-Jordan circuit as a storage register; it is considered the first programmable, electronic, digital computer, although its existence was kept secret until the 1970's.

Exercises

Investigate the behavior of a latch built with NOR gates instead of the NAND gates used in the latch. Use this new latch to build a gated D latch.

There are several other types of flip-flops besides the D. Perhaps the most general is the JK flip-flop, which has two inputs, traditionally named and , along with a clock input and the complementary and outputs. When and are both 0 and a clock pulse arrives, the state does not change. When only is 1, the new state will be 1; when only is 1, the new state will be 0 (so sets and resets the flip-flop). Finally, when both and are 1, the clock pulse will cause the state to toggle—that is, it will switch to the negation of its previous state. Here is the characteristic table of the JK flip-flop, using to indicate "don't care" inputs:

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | X | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | X | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

- Draw a timing diagram that shows the behavior of the JK flip-flop.

- Give an excitation table for the JK flip-flop.

- Show how to construct a JK flip-flop using a D flip-flop plus a few extra gates. (Hint: Combine the and inputs with the current outputs and to generate an appropriate input.)

- Random-access memory (RAM) devices can be made from a quantity of flip-flops plus a few extra components such as multiplexers and demultiplexers. To store individually-addressable bits, you need one D type flip-flop per bit. The inputs can all be connected to an incoming data line; if each flip-flop's clock signal is driven by one line of a -bit demultiplexer whose input signal is the AND of the system clock signal and a "write enable" input, then the flip-flop selected by the address lines will be loaded with the desired data only if a write is enabled at the rise of the clock. Connecting the outputs of the flip-flops to a multiplexer, whose select lines are also driven by the -bit address, will cause the contents of the selected bit to be passed to the output of the MUX. Use this description to draw a 16-bit RAM circuit, then show how to expand it to store four bits at each address.

- In fact, since a physical device can only be an approximation of a pure logic gate, it is more likely that the output would hover around some intermediate level, neither high nor low.↩

- A nice variation of the main-secondary design uses an for one layer and an latch for the other, so there is no need to invert the clock between the two halves, but the operation is a little harder to read.↩