Nondeterministic Finite-State Automata

(Content adapted from Critchlow & Eck)

As mentioned briefly above, there is an alternative school of though as to what

properties should be required of a finite-state automaton's transition function.

Recall our motivating example of a C++ compiler and a legal if statement.

In our description, we had the compiler in an "expecting a )" state; on

seeing a ), the compiler moved into an "expecting a { or a legal

statement" state. An alternative way to view this would be to say that the

compiler, on seeing a ), could move into one of two different states: it could

move to an "expecting a {" state or move to an "expecting a legal

statement" state. Thus, from a single state, on input ), the compiler has

multiple moves. This alternative interpretation is not

allowed by the DFA model.

A second point on which one

might question the DFA model is the fact that input must be consumed for the

machine to change state.

Think of the syntax for C++ function declarations. The return type of a

function need not be specified (the default is taken to be int). The

start state of the compiler when parsing a function declaration might be

"expecting a return type"; then with no

input consumed, the compiler can move to the state "expecting a legal function

name". To model this, it might seem reasonable to allow transitions that do

not require

the consumption of input (such transitions are called

-transitions). Again, this is not supported by the DFA abstraction.

There is, therefore, a second class of finite-state automata that people

study, the class of nondeterministic finite-state automata.

A nondeterministic finite-state automaton (NFA) is the same as a deterministic finite-state automaton except that the transition function is no longer a function that maps a state-input pair to a state; rather, it maps a state-input pair or a state- pair to a set of states. No longer do we have , meaning that the machine must change to state if it is in state and consumes an . Rather, we have , meaning that if the machine is in state and consumes an , it might move directly to any one of the states . Note that the set of next states is defined for every state and every input symbol , but for some 's and 's it could be empty, or contain just one state (there don't have to be multiple next states). The function must also specify whether it is possible for the machine to make any moves without input being consumed, i.e., must be specified for every state . Again, it is quite possible that may be empty for some states : there need not be -transitions out of .

Formally, a nondeterministic finite-state automaton is specified by 5 components: where

- , , and are as in the definition of DFAs;

- is a transition function that takes pairs and maps each one to a set of states. To say means that if the machine is in state and the input symbol is consumed, then the machine may move directly into any one of states . The function must also be defined for every pair. To say means that there are direct -transitions from state to each of .

The formal description of the function is .

The function describes how the machine functions on zero or one input symbol. As with DFAs, we will often want to refer to the behavior of the machine on a string of inputs, and so we use the notation as shorthand for "the set of states in which the machine might be if it starts in state and consumes input string ". As with DFAs, is determined by the specification of . Note that for every state , contains at least , and may contain additional states if there are (sequences of) -transitions out of .

We do have to think a bit carefully about what it means for an NFA to accept a

string . Suppose contains both accepting and non-accepting

states, i.e., the machine could end in an accepting state after consuming ,

but it might also end in a non-accepting state. Should we consider the machine

to accept , or should we require every state in to be

accepting before we admit to the ranks of the accepted? Think of the C++

compiler again: provided that an if statement fits one of the legal

syntax specifications, the compiler will accept it. So we take as the

definition of acceptance by an NFA: A string is accepted by an NFA provided

that at least one of the states in is an accepting state.

That is, if there is some sequence of steps of the machine that consumes

and leaves the machine in an accepting state, then the machine accepts .

Formally:

Let be a nondeterministic finite-state automaton. The string is accepted by iff contains at least one state .

The language accepted by , denoted , is the set of all strings that are accepted by : .

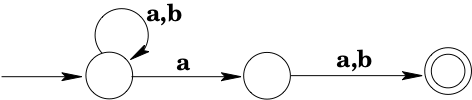

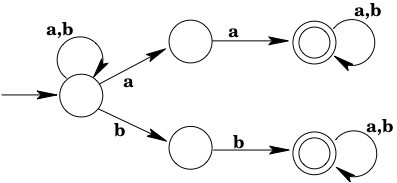

Example: The NFA shown below accepts all strings of 's and 's in which the second-to-last symbol is .

Connection with Deterministic Finite-State Automata

It should be fairly clear that every language that is accepted by a DFA is also accepted by an NFA. Pictorially, a DFA looks exactly like an NFA (an NFA that doesn't happen to have any -transitions or multiple same-label transitions from any state), though there is slightly more going on behind the scenes. Formally, given the DFA , you can build an NFA where 4 of the 5 components are the same and where every transition has been replaced by .

But is the reverse true? Can any NFA-recognized language be recognized by a DFA? Look, for example, at the language in the example above. Can you come up with a DFA that accepts this language? Try it. It's pretty difficult to do. But does that mean that there really is no DFA that accepts the language, or only that we haven't been clever enough to find one?

It turns out that the limitation is in fact in our cleverness, and not in the power of DFAs.1

Theorem: The Subset Construction

Every language that is accepted by an NFA is accepted by a DFA.Proof: Suppose we are given an NFA , and we want to build a DFA that accepts the same language. The idea is to make the states in correspond to subsets of 's states, and then to set up 's transition function so that for any string , corresponds to ; i.e., the single state that gets you to in corresponds to the set of states that could get you to in . If any of those states is accepting in , would be accepted by , and so the corresponding state in would be made accepting as well.

So how do we make this work? The first thing to do is to deal with a start state for . If we're going to make this state correspond to a subset of 's states, what subset should it be? Well, remember (1) that in any DFA, ; and (2) we want to make correspond to for every . Putting these two limitations together tells us that we should make correspond to . So corresponds to the subset of all of 's states that can be reached with no input.

Now we progressively set up 's transition function by repeatedly doing the following:

Find a state that has been added to but whose out-transitions have not yet been added. (Note that initially fits this description.) Remember that the state corresponds to some subset of 's states.

For each input symbol , look at all 's states that can be reached from any one of by consuming (perhaps making some -transitions as well). That is, look at . If there is not already a DFA state that corresponds to this subset of 's states, then add one, and add the transition to 's transitions.

The above process must halt eventually, as there are only a finite number of states in the NFA, and therefore there can be at most states in the DFA, as that is the number of subsets of the NFA's states. The final states of the new DFA are those where at least one of the associated NFA states is an accepting state of the NFA.

Can we now argue that ? We can, if we can argue that corresponds to for all : if this latter property holds, then iff is accepting, which we made be so iff contains an accepting state of , which happens iff accepts i.e., iff .

So can we argue that does in fact correspond to for all ? We can, using induction on the length of .

First, a preliminary observation. Suppose , i.e., is the string followed by the single symbol . How are and related? Well, recall that is the set of all states that can reach when it starts in and consumes : for some states . Now, is just with an additional , so where might end up if it starts in and consumes ? We know that gets to or or , so gets to any state that can be reached from with an (and maybe some -transitions), and to any state that can be reached from with an (and maybe some -transitions), etc. Thus, our relationship between and is that if , then . With this observation in hand, let's proceed to our proof by induction.

We want to prove that corresponds to for all . We use induction on the length of .

Base case: Suppose has length 0. The only string with length 0 is , so we want to show that corresponds to . Well, , since in a DFA, for any state~. We explicitly made correspond to , and so the property holds for with length 0.

Inductive case: Assume that the desired property holds for some number , i.e., that corresponds to for all with length . Look at an arbitrary string with length . We want to show that corresponds to . Well, the string must look like for some string (whose length is ) and some symbol . By our inductive hypothesis, we know corresponds to . We know is a set of 's states, say .

At this point, our subsequent reasoning might be a bit clearer if we give explicit names to (the state reaches on input ) and (the state reaches on input ). Let , and let . We know, because , there must be an -transition from to . Look at how we added transitions to : the fact that there is an -transition from to means that corresponds to the set of 's states. By our preliminary observation, is just . So (or ) corresponds to , which is what we wanted to prove. Since was an arbitrary string of length , we have shown that the property holds for .

Altogether, we have shown by induction that corresponds to for all . As indicated at the very beginning of this proof, that is enough to prove that . So for any NFA , we can find a DFA that accepts the same language.

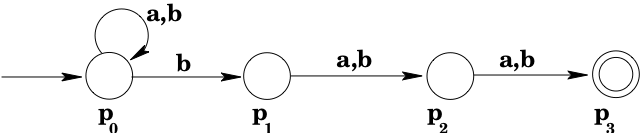

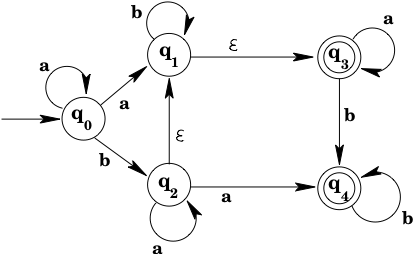

Example: Consider the NFA shown below.

We start by looking at , and then add transitions and states as described above.

so .

will be , which is , so .

will be , which is , so we need to add a new state to the DFA; and add to the DFA's transition function.

will be unioned with since . Since , we need to add a new state to the DFA, and a transition .

will be unioned with , which gives , which again gives us a new state to add to the DFA, together with the transition .

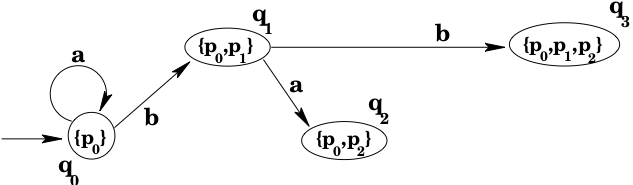

At this point, our partially-constructed DFA looks as shown below:

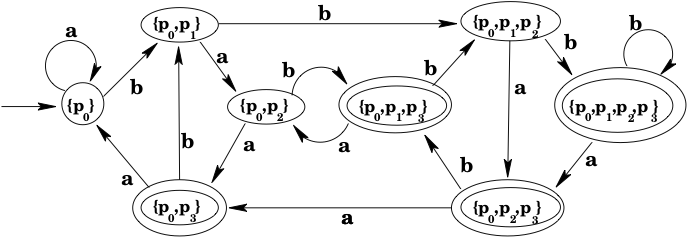

The construction continues as long as there are new states being added, and new transitions from those states that have to be computed. The final DFA is shown below.

Exercises

What language does the NFA in the above example accept?

Answer

Strings of 's and 's where the third-from-last character is .

Give a DFA that accepts the language accepted by the following NFA.

- Give a DFA that accepts the language accepted by the following NFA. (Be sure to note that, for example, it is possible to reach both and from on consumption of an , because of the -transition.)

- The fault, dear reader, is not in our , but in ourselves.↩